According to Tolowa oral histories, the Athapaskan people of southern Oregon and northern California arrived from the north in ancient times, traveling by canoe. Linguists estimate that they arrived in the region about 700 years ago.

The Athapaskans lived in the valleys on the Rogue and Illinois rivers, where the land is steep and mountainous, and along the northern California and southern Oregon coasts. Many made their homes along the Coquille and Umpqua rivers.

A number of tribes and bands in southwestern Oregon spoke dialects of the Athapaskan language; as can best be determined, the dialects included Upper Umpqua, Upper Coquille, Kwatami, Yukichetunne, Chemetunne, Mikonotunne, Chasta Costa, Tututni, Chetleshin, Khwaishtunnetunne, Galice, Applegate, and Chetco. The Tolowa dialect was spoken in northern California. Many of these dialects are extinct and only speakers of Tututni and Tolowa remain.

The Athapaskans participated in an extensive sociopolitical trade network, and their seasonal rounds consisted of moving to temporary camps to harvest, fish, and hunt. Coastal tribes set up summer fishing camps, where they caught smelt, picked strawberries, and hunted for otter. Later in the year, they moved into the Coast Range to hunt for elk and gather plants for basket-making.

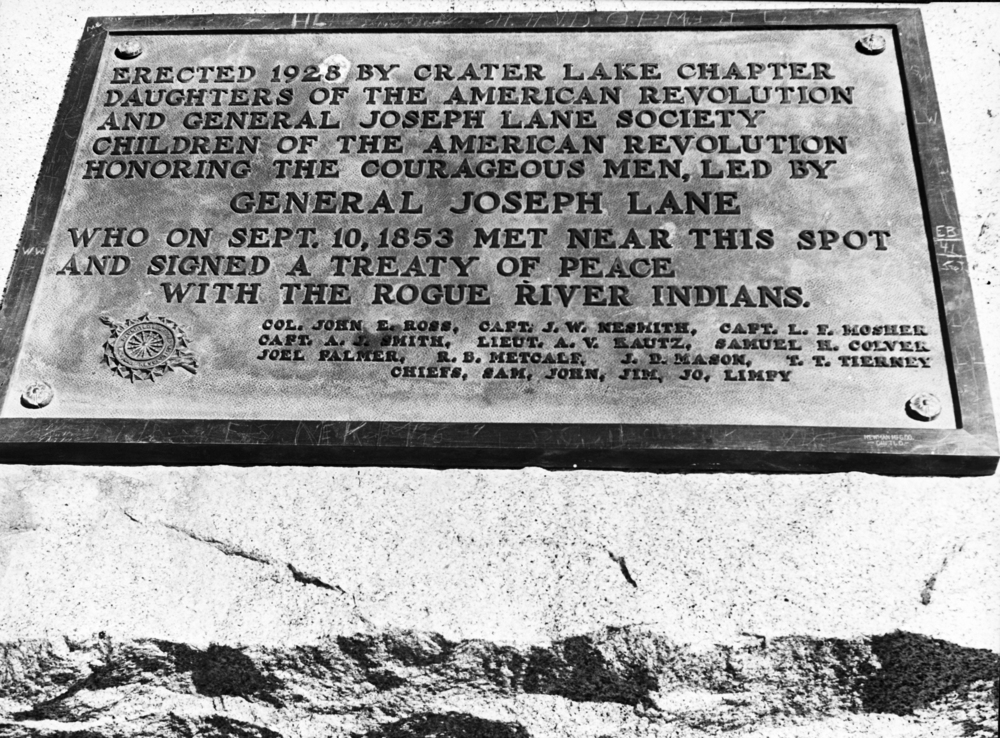

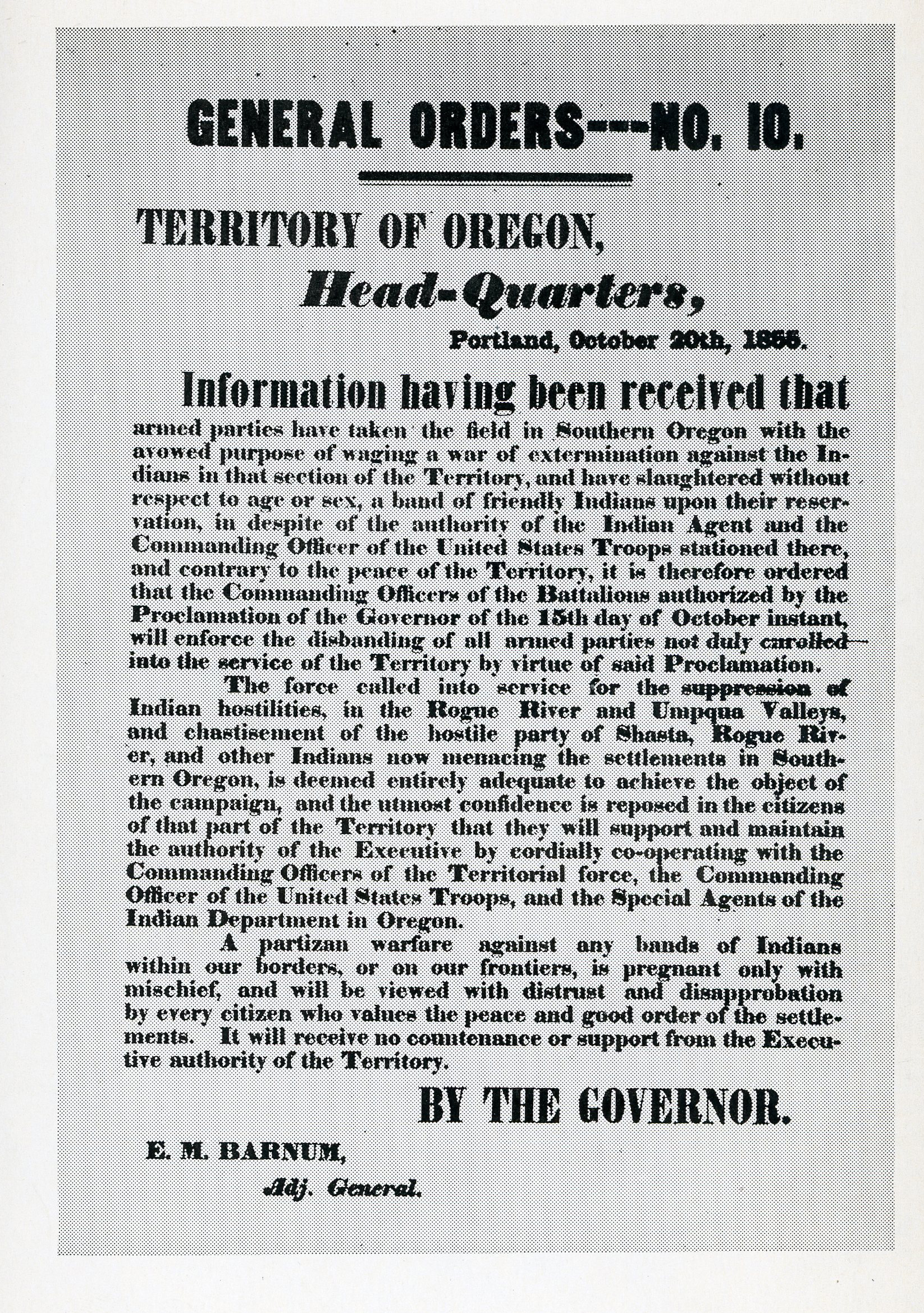

Many Athapaskan villages were situated on prime river terraces, land that was coveted by American settlers and miners. The Rogue River Indian wars—an effort by Americans to exterminate Native peoples in the region—began in 1850 as a series of skirmishes with early miners and white settlers. In 1853, the battle of Evans Creek was waged near Battle Mountain, and two years later warriors fought gold miners at Applegate Creek to protect tribal homelands.

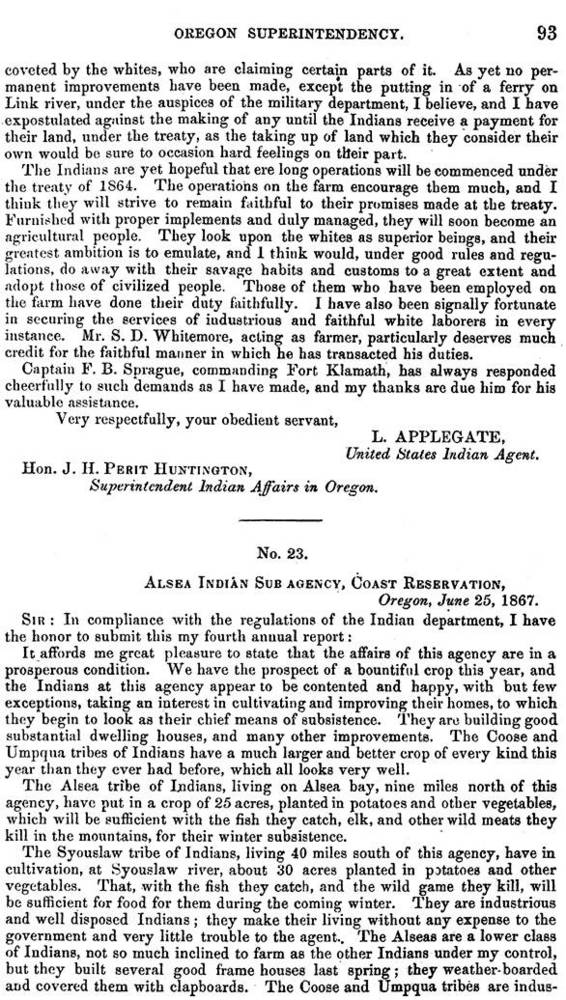

The last of the Rogue River wars was sparked by the delay of the U.S. Congress to ratify the second round of Oregon treaties. Gen. John E. Wool, commander of the Department of the Pacific in 1855-1856, vilified the actions of the militia, blaming it for much of the warfare and for invading tribal territories. "Whilest I was in Oregon," Wool wrote on February 12, 1856, "it was reported to me, that many citizens, with due proportion of volunteers, . . . advocated the extermination of the Indians."

Between 1853 and 1856, Athapaskan tribes and bands were party to treaties negotiated between agents of the federal government and tribal headmen. The ratified treaties are with the Cow Creek Band of Umpqua (November 19, 1853), the Rogue River Tribes (September 10, 1853, and November 11, 1854), the Chasta Costa (November 18, 1854), and the upper Umpqua and (non-Athapaskan) Kalapuya (November 29, 1854). The coastal bands of Athapaskans were party to the unratified Coast Treaty of 1855. The treaties remain in effect today and constitute the foundation for many of the tribes' sovereign rights.

In 1854, many Rogue River peoples were removed to the Table Rock Reservation, north of the Rogue River. In 1855, Superintendent of Indian Affairs Joel Palmer gathered many of the Athapaskans at Port Orford and transported 1,400 of them to the Grand Ronde Reservation on two ships. Another group was marched to Siletz Agency on the Coast Reservation, a long and harsh trek that, along with the forced movement of a group from the Table Rock Reservation to the Grand Ronde Reservation, is characterized as the "Oregon Trail of Tears." In 1857, two-thirds of the Rogue River Indians were removed to the Siletz Agency.

Over successive generations, members of the Rogue River and other Athapaskan-speaking tribes on the Grand Ronde and Siletz reservations intermarried with members of other tribes. Today, most of the tribal members of those reservations have some Athapaskan ancestry.

In 1954, the Western Oregon Indian Termination Act, Public Law 588, ended the federal recognition of all western Oregon tribes. In 1977, the Confederated Tribes of Siletz was restored; the Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde Community of Oregon was restored in 1983. Descendants of the southern Oregon Athapaskans are members of these two tribes. There are three rancherias of the Tolowa people in California, and a number of unaffiliated Tututni and Rogue River people live in southwestern Oregon.

Since restoration, there has been a steady growth of the Athapaskan culture in western Oregon and northern California. The Smith River Rancheria, six miles south of the Oregon state line, constructed a dancehouse in the 1980s, and the Siletz constructed a plankhouse in the 1990s. The houses provide a venue for traditional cultural and spiritual ceremonies and activities, such as the seasonal feather dances or Nee-dash. Athapaskan language dialects are also being revitalized, with the Tolowa and Tututni dialects now being taught in Smith River, California, and Siletz, Oregon.

-

![]()

Athapaskan mother and child, c. 1900.

Courtesy Library of Congress

Related Entries

-

![Alsea Subagency of Siletz Reservation]()

Alsea Subagency of Siletz Reservation

In September 1859, Joel Palmer, the Superintendent of Indian Affairs fo…

-

![Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde (essay)]()

Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde (essay)

The Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde Community of Oregon is a confede…

-

![Council of Table Rock]()

Council of Table Rock

The 1853 Council of Table Rock negotiated a peace treaty between repres…

-

![Rogue River War of 1855-1856]()

Rogue River War of 1855-1856

The final Rogue River War began early on the morning of October 8, 1855…

-

![Termination and Restoration in Oregon (essay)]()

Termination and Restoration in Oregon (essay)

Of the federal-Indian policies introduced to American Indians, terminat…

Related Historical Records

Further Reading

Bancroft, H.H. The Works of Hubert Howe Bancroft. Vol. 2: 1848-1888. Part 1, Oregon. San Francisco: Bancroft Publishing, 1883. www.gutenberg.org/browse/authors/b#a944.

Beckham, Stephen Dow. "History of Western Oregon Since 1846." In Handbook of North American Indians. Vol. 7. Northwest Coast. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 1990.

Colvig, William. Indian Wars of Southern Oregon, 1902. Southern Oregon Digital Archives. http://soda.sou.edu/.

Miller, Jay, and William Seaburg. "Athapaskans of Southwestern Oregon." In The Handbook Of North American Indians. Vol. 7. Northwest Coast. Ed. Wayne Suttles. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 1990.