Two hundred and fifty years after the place-name Oregon appeared on maps and other documents, its etymology remains uncertain. Jonathan Carver’s widely read Travels through the Interior Part of North America in 1778 mentions that one of the rivers he had learned about from Indians was “the Oregon, or River of the West.” That was the first literary use of the name, and it was long supposed that Carver had introduced the word into English.

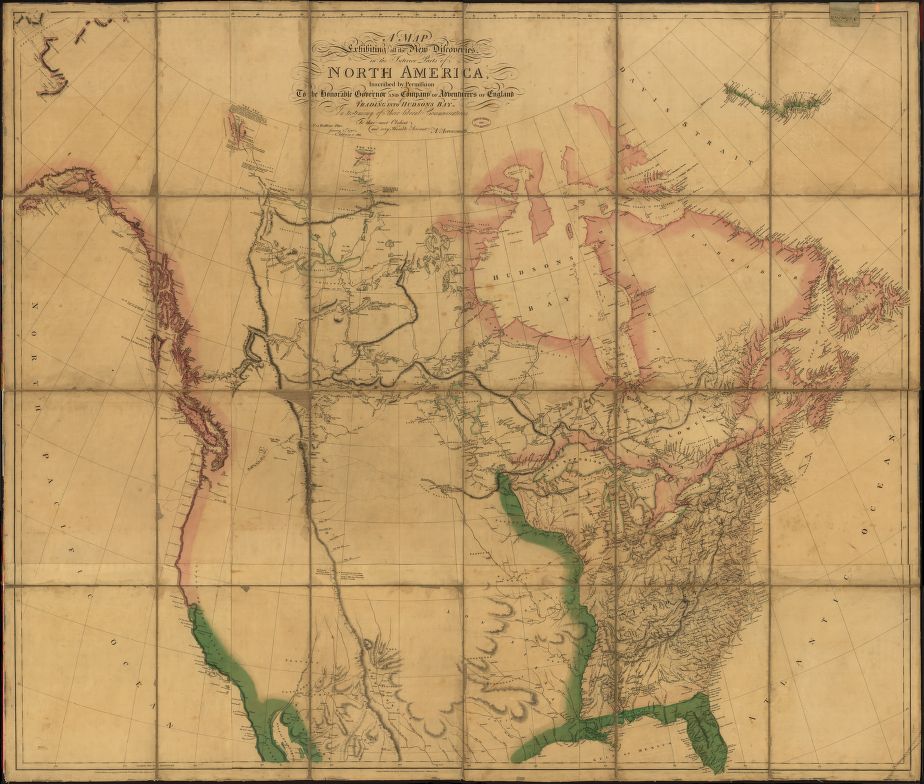

Not long afterward, the River Oregon appeared on maps by Aaron Arrowsmith. His 1790 map showed the “R. Oreġan” flowing to the Pacific, and later maps depict the “R. Oreġan or Columbia R.” extending to the headwaters of the Missouri. Aware of these maps, Thomas Jefferson in June 1803 instructed Meriwether Lewis to “explore the Missouri river, & such principal stream of it as by its course and communication with the waters of the Pacific ocean whether the Columbia, Oregon, Colorado or any other river.” A few years later, the poet William Cullen Bryant, still in his teens, would invoke the rolling Oregon River in his poem “Thanatopsis”—linking it with the Barcan desert of North Africa as symbols of West and East. The name of the river soon became extended in American usage for the region of the Pacific Northwest north of 42°N latitude and south of 54°40′N latitude. The British referred to this as the Columbia District.

During the nineteenth century, the name Oregon was still the subject of much speculative etymology. From present-day California to Vancouver Island in British Columbia, the West Coast had been colonized by the Spanish in the early sixteenth century, so some early theories were that Oregon had been adapted either from oregano, an herb, or orejon, a word meaning “big ears” that was believed to have been used by Spanish explorers to refer to some indigenous people. As early as 1900, Portland Oregonian editor Harvey Scott dismissed both theories as lacking documentary evidence and chided schoolbooks for including the information. Scott himself had at one time promoted the idea that Oregon came from Aragon, a French synonym for Spain, but he dismissed that, too, as “mere conjecture.”

In the early twentieth century, interest in the name remained so strong that the Oregon Historical Society dedicated an issue of the Oregon Historical Quarterly to the topic in 1920. Idaho State University professor John Rees proposed a Shoshone origin for the name, based in part on Jonathan Carver’s contact with the Sioux. Rees proposed that the name came from the two words, ogwa (river) and pe-on (west), which would have meant something like ‘River of the West’. In 1922, historian Jacob Meyers also suggested a Sioux origin for the name but imagined that Carver had adapted it from the phrase Owah-menah Wakan, which translated as ‘river of the slaves’ and would have been shortened by some Sioux speakers to O'Wakan.

In 1920, engineer William H. Galvani returned to the idea of a Spanish origin for the name. He proposed that Ouragan was the name applied by religious refugees from Spain who associated the Northwest geography and climate with the Kingdom of Aragon. Indians, he supposed, would have learned the word from the Spaniards.

At about the same time, banker and historian Thomas Coit Elliott suggested that the name was an adaptation of the French word ouragan ‘hurricane’, which he attributed to French traders. Elliott had uncovered a document in a 1765 proposal written by colonial soldier Major Robert Rogers, who was petitioning King George III to fund an expedition to find the Northwest Passage by way of “the River called by the Indians Ouragon.” The king declined, but Rogers later helped establish an expedition that included Jonathan Carver. Elliott believed that Rogers, who lived in the Great Lakes region, might have heard the word from French traders or from Native people who were in contact with the French.

Historian George R. Stewart, at the University of California, Berkeley, also proposed a French source, calling attention to a 1709 French map on which the name of the Wisconsin River, the Ouisiconsink, was clumsily displayed on two lines with “Ouaricon” on one line and “sint” below. While there is no evidence of Rogers using the map, Stewart thought Rogers might have “heard that on 'some old map' there was a river of that name flowing toward the west.”

Two more recent proposals address Rogers’s attribution of the word Ouragan to Natives. Archeologist Scott Byram and anthropologist David G. Lewis argue that the word ooligan might have been transmitted to the Great Lakes region by means of a complex indigenous trade network that extended across North America. Rogers’s description of the route to the river from the Great Lakes follows the trading network known as the “grease trails,” across the northern Rockies to the upper Fraser River. This was the habitat of the oil-rich candlefish, called ooligan in the Chinook Jargon trade language used in the Northwest. Algonquian speakers from the east of the Rockies would have been familiar with the word ooligan, Byram and Lewis suggest, and the word for the fish might have been extended to refer to the river as well. They also point to well-documented changes in pronunciation that would render the word as oorigan in some Algonquian dialects.

Linguist Ives Goddard and historian Thomas Love also propose Algonquian as the immediate source of Rogers’s Ouragon. Their view is that it was adapted from the Mohegan wauregan ‘the beautiful’, used by Connecticut Indians as the name of the Allegheny–Ohio River. Rogers had used Connecticut Indians as troops in the French and Indian Wars and could have become acquainted with the word from them. Rogers also might have consulted a French map showing a “Belle Riv” flowing to the west beyond the Missouri, and Goddard and Love suspect that Rogers used the word he already knew to mean ‘beautiful river’ to also refer to this supposed route to the Pacific. Perhaps, they conjecture, Rogers had learned from the Mohegans that there was another “beautiful river” in addition to the Ohio, or perhaps he was stretching the truth to bolster his petition for funds for exploration.

As Goddard and Love note, the connection of Oregon to wauregan is an old idea, dating back to an 1879 study by J. Hammond Trumbull. It may turn out to be the last word on the toponym Oregon, or there may yet be further discoveries—letters and maps found, or cultural connections made. For now, we can safely say that the name originated from Major Robert Rogers rendering of a Native word for the water route to the Pacific.

-

!["A map exhibiting all the new discoveries in the interior parts of North America"]()

1802 Arrowsmith map, detail.

"A map exhibiting all the new discoveries in the interior parts of North America" Courtesy Library of Congress, 2001620920

-

!["A map exhibiting all the new discoveries in the interior parts of North America"]()

Arrowsmith map, 1802, full.

"A map exhibiting all the new discoveries in the interior parts of North America" Courtesy Library of Congress, 2001620920

Related Entries

Further Reading

Elliott, T. C. "Jonathan Carver's Source for the Name Oregon." Quarterly of the Oregon Historical Society 23 (1922): 53-69.

Hayes, Derek. Historical Atlas of the Pacific Northwest: Maps of Exploration and Discovery: British Columbia, Washington, Oregon, Alaska, Yukon. Seattle, Wash.: Sasquatch Books, 1999.

Allen, John Logan. Passage Through the Garden; Lewis and Clark and the Image of the American Northwest. Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 1974.

Thomas Jefferson and Early Western Explorers. Transcribed and Edited by Gerard W. Gawalt, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress. http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/lewisandclark/transcript57.html]

Scholl, John William. "On the Two Place-Names in 'Thanatopsis.' Modern Language Notes 28.8 (December 1913): 247-249.

Scott, H. W. “Not Marjoram. The Spanish Word "Oregano" Not the Original of Oregon.” The Quarterly of the Oregon Historical Society 1.2 (1900): 165-168.

Rees, J. E. “Oregon-Its Meaning, Origin and Application." The Quarterly of the Oregon Historical Society 21.4 (1920): 317-331.

Lewis, William S. “Some Notes and Observations on the Origin and Evolution of the Name Oregon as Applied to the River of the West.” Washington Historical Quarterly 17.3 (1926): 218-222.

Meyer, J.A. “River of the Slaves or River of the West.” Washington Historical Quarterly 13 (1922): 4, 282-3.

Galvani, W.H. "The early explorations and the origin of the name of the Oregon country." Oregon Historical Quarterly 21.4 (1920): 332-340.

Elliott, T.C. “The Strange Case of Jonathan Carver and the Name Oregon.” Quarterly of the Oregon Historical Society 21 (1920): 341-68.

Elliott, T. C. “The Origin of the Name Oregon.” Quarterly of the Oregon Historical Society 22 (1921): 91-115.

Stewart, G. R. “The Source of the Name ‘Oregon’.” American Speech 19.2 (1944): 115-117.

Stewart, G. R. “Ouaricon Revisited.” Names 15.3 (1967): 166-172.

Byram, Scott, and David G. Lewis. “Ourigan: Wealth of the Northwest Coast.” Oregon Historical Quarterly 102:2 (2001): 126-57.

Ives, Goddard, and Thomas Love. “Oregon, the Beautiful.” Oregon Historical Quarterly 105.2 (2004): 238-259.

Trumbull, J. Hammond. “Oregon: The Origin and Meaning of the Word.” The Magazine of American History, with Notes and Queries 3 (1879): 36-8.