During the early nineteenth century, upwards of thirty Native American villages were documented in the Portland Basin (present-day Multnomah, Clark, Clackamas, and east Columbia Counties). Most of the villages were sited on riverbanks and in wetlands along the Columbia and Willamette Rivers and were occupied by people who spoke dialects of a Chinookan language or languages. In their journals, Meriwether Lewis and William Clark classified the villages under three headings: “Wappato Indians” for those villagers around Sauvie Island and on the Columbia River between present-day Kalama and Vancouver; "Sha-ha-la" (for šáx̣l(a) ‘upstream’) from Vancouver to the Cascades Rapids; and the peoples of the lower Willamette River, including the Clackamas River and Willamette Falls. Non-Chinookan villages, mostly upstream on tributaries to the Columbia, were home to Sahaptin-speaking Upper Cowlitz and Klikatat [var: Klickitat] in present-day Clark County, Clatskanie in present-day Columbia County, and Molala in present-day Clackamas County.

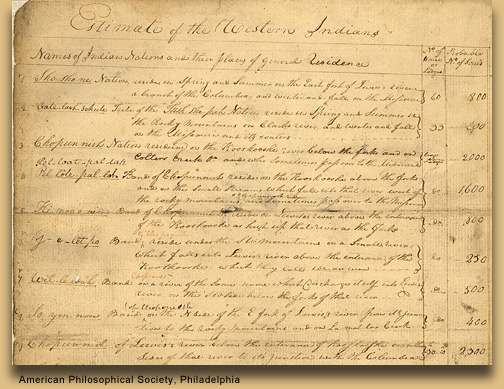

Lewis and Clark’s “Estimate of the Western Indians,” the most complete listing of Portland Basin villages, appears in two versions in their journals, with different population estimates for many Chinookan villages. They estimated the population of the Portland Basin peoples at 4,840 (Estimate 1) and 10,940 (Estimate 2). The most likely explanation for the variable numbers is that they represent seasonal populations that the explorers observed during their two transits of the Wappato Valley. At first transit, from late October to early November 1805, most local people had retired to their winter villages; at the second transit, from late March to early April 1806, the population was augmented by visitors who had arrived to take advantage of the seasonal Columbia River fisheries (sequentially, eulachon, sturgeon, chinook, and coho salmon).

Lewis and Clark’s estimates date to a generation after a major smallpox epidemic that had significantly diminished the Native population. The Portland Basin villages continued as functioning entities until the early 1830s, when annual summer epidemics of “fever and ague” took most of the people to their graves. After 1835, most riverbank villages were abandoned, and non-Chinookan interior peoples moved closer to the rivers. Villages of Chinookan survivors, often mixed with newcomers, continued at Wakanasisse below present-day Vancouver, West Linn, Gladstone (Clackamas), and the Upper Cascades. A Cascades seasonal village was located on the south bank of the Columbia River opposite present-day Vancouver. All villages were vacated in the mid-1850s, when most surviving Native people in the Portland Basin were removed to the Grand Ronde and Yakama Reservations.

Archaeologically, the record on the early 1800s Portland Basin villages is mixed. Most of the villages were destroyed soon after they were abandoned, and only a few survived to be excavated by professional archaeologists. Multnomah village, for instance, was burned by the Hudson’s Bay Company after the epidemics, and the site itself has mostly washed away. Most exposed sites were destroyed by looters after 1830, and some were excavated by the Oregon Archaeological Society in the mid-1900s (particularly along Lake River). Only a few survived to be examined by professional archaeologists after 1980, including Cathlapotle, Meier near Scappoose, Clahclellar at the Middle Cascades, the Portland St. Johns sites, and the “Sunken Village” at the Sauvie Island bridge. Several seasonal and nonsettlement sites—for example, resource areas and cemeteries—suffered similar fates.

Table of Portland Basin Chinookan Villages in the 1800s

- Wapato Valley to The Cascades: according to Lewis and Clark’s Estimate:

“Wappato Indians”

|

Name |

Phonemic Spelling |

Location |

Population |

|

Callamaks |

gaɬákʼalama ‘those of the rock’ |

Kalama R mouth |

200 |

|

Cathlahaw’s |

|

Kalama R/Deer Island |

|

|

Quathlapohtle |

gáɬapʼuƛx ‘those of nápʼuƛx (Lewis R)’ |

|

300/900 |

|

Clannarminnamun, Cathlaminimin |

|

lower Multnomah Channel |

280 |

|

Cathlahcumup |

gaɬáqʼmap ‘those of the mound’ |

Multnomah Channel |

150/450 |

|

Claninnata |

|

Multnomah Channel |

100/200 |

|

Clackstar Nation |

ɬáqstʼax̣ |

Scappoose Plains |

350/1200 |

|

Cathlahnahquiah |

gaɬánaqʷaix, naqʷáix |

Fort William |

150/170 |

|

Cathlahcommahtup |

|

Sauvie Isl bridge |

70/170 |

|

Nemalquinner |

nimáɬx̣ʷinix |

lower Willamette R |

100/200 |

|

Clannahqueh |

|

Sauvie Isl Columbia R bank |

130 |

|

Multnomah |

máɬnumax̣ ‘those towards the water’ |

Sauvie Isl Columbia R bank |

200/800 |

|

Shoto |

|

Lake River |

160/460 |

|

Nechacolee, Nechacokee |

ničáqʷli ‘stand of pines’ (?) |

Blue Lake |

100 |

|

Total population: |

|

|

4840/10940 |

(Clackamas River and Willamette Falls)

|

Clarkamus Nation |

giɬáqʼimaš, gitɬáqʼimaš ‘those of niqʼímaš (Clackamas R)’ |

Clackamas R |

800/1800 |

|

Cushhooks |

kʼášxəkš |

Abernethy Cr |

250/650 |

|

Charcowah |

čaká·wa (Molala name) |

above Willamette Falls |

200 |

“Shahala Nation” (šáx̣l(a) ‘upriver, above’; total population: 1300/2800)

|

Neerchokioo |

|

w of Portland Airport |

|

Wahclelah, Clahclellars |

waɬála ‘small lake’; ɬaɬála, gaɬaɬála ‘those of waɬála’ |

n side of Lower, Middle, and Upper Cascades (multiple locations) |

|

Yehuh |

wáyaxix ‘his face place’ |

s side of Upper Cascades |

- Noted in later sources.

|

Historical spelling/Source |

Phonemic Spelling |

Location |

|

Naiakookwie (Gibbs, 1853) |

náiaguguix |

St. Helens |

|

Scappoose (Gibbs, 1853) |

sqə́pus |

Milton Cr (?) |

|

Namouite (Ross, 1821) |

namúitk |

Sauvie Isl, Columbia River bank |

|

Gah̅láwaks͡hĭn (Curtis, 1911) |

gaɬáwakšin ‘those of the dam (wákšin)’ |

St. Johns, Portland |

|

Wakanasisse (Gibbs, 1853) |

wákʼanasisi ‘diver ducks’ |

below Vancouver |

|

Clowewalla (Henry, 1814) |

ɬáwiwala, gaɬawálamt (‘those of wálamt’) |

Willamette Falls |

|

Wasuscally (Ross, 1821) |

gaɬawašúxʷal ‘those of wašúxʷal)’ |

Washougal, WA |

|

Skamányăk (Curtis, 1911) |

skʼmániak ‘obstructed’ |

between Middle & Upper Cascades |

|

Wat lala (Hale, 1841) |

waɬála ‘small lake’ |

Wauna Lake

|

-

![]()

Estimate of Western Indians, Lewis and Clark.

Courtesy American Philosophy Association, Philadelphia

-

Cathlapotle, modern plankhouse.

Courtesy U.S. Depatment of Fish & Wildlife

-

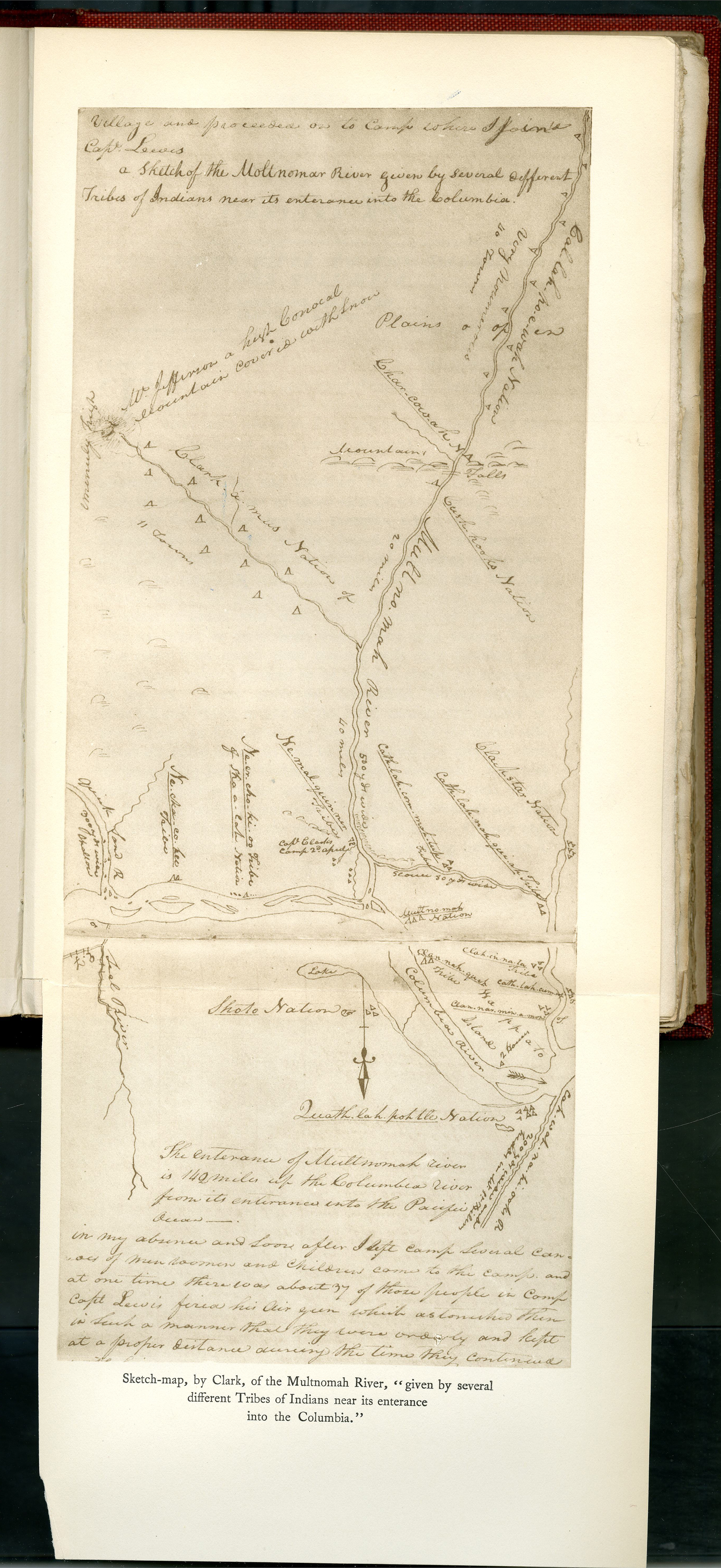

![]()

Clark's sketch of the Multnomah River, from his journals.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib.

-

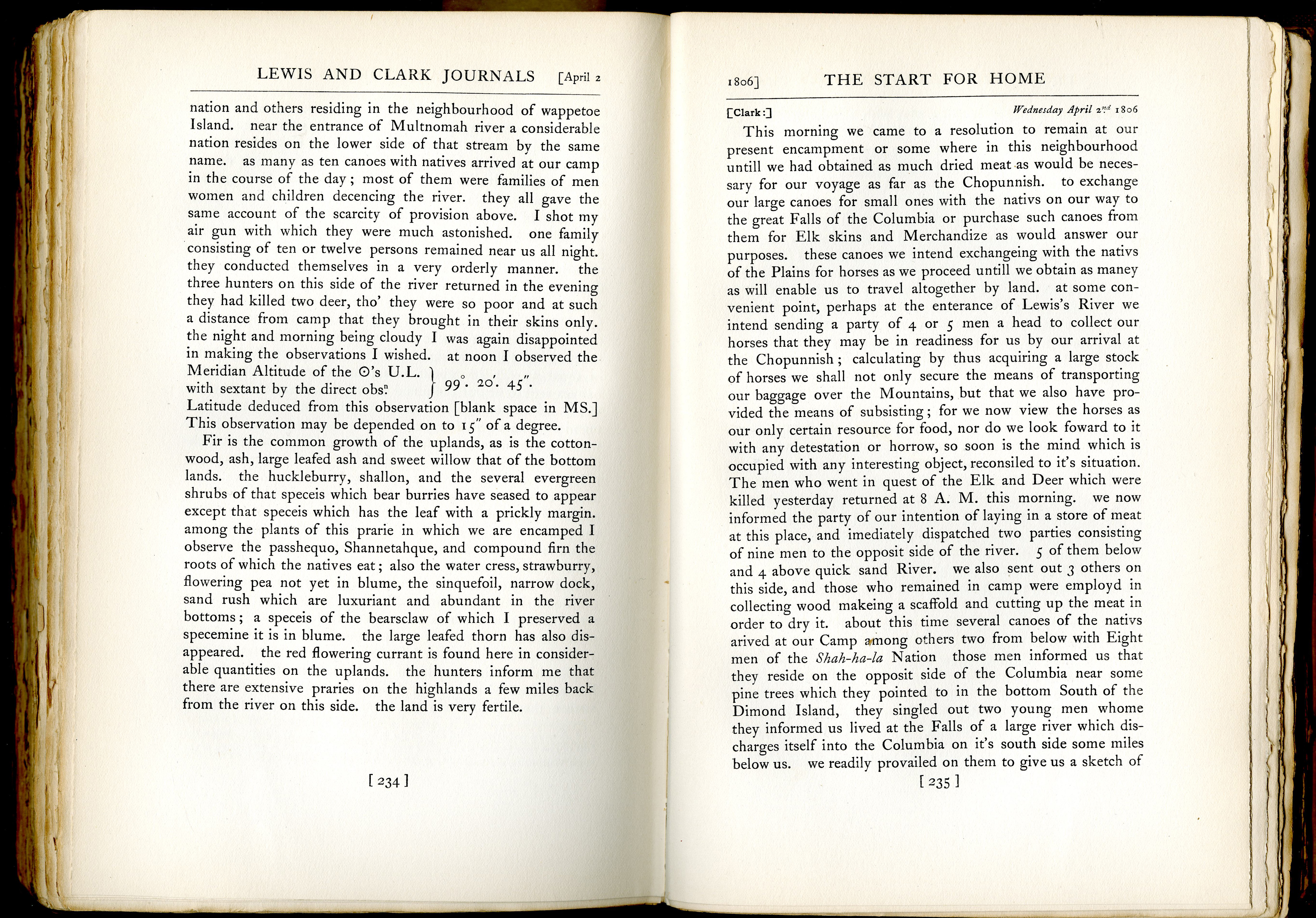

![Click on documents tab to see longer journal entry on Lewis and Clark's observations.]()

Account of Sauvie Island and inhabitants.

Click on documents tab to see longer journal entry on Lewis and Clark's observations. Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib.

Documents

Related Entries

-

Cathlapotle

Cathlapotle is the archaeological site of a major Chinookan town locate…

-

![Disease Epidemics among Indians, 1770s-1850s (essay)]()

Disease Epidemics among Indians, 1770s-1850s (essay)

In 1972, historian Alfred Crosby introduced the term Columbian Exchange…

-

![Multnomah (Sauvie Island Indian Village)]()

Multnomah (Sauvie Island Indian Village)

"Multnomah" is a word familiar to Oregonians as the name of a county an…

-

![Native American Art of the Wapato Valley]()

Native American Art of the Wapato Valley

Sauvie Island, at the confluence of the Willamette and Columbia Rivers,…

-

![Wapato (Wappato) Valley Indians]()

Wapato (Wappato) Valley Indians

Lewis and Clark called them the "Wappato Indians," the people who inhab…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Boyd, Robert, and Yvonne Hajda. “Seasonal Population Movement along the Lower Columbia River: The Social and Ecological Context.” American Ethnologist 14:2 (1987): 309-26.

Moulton, Gary, ed. The Journals of the Lewis & Clark Expedition. Vols. 5-7. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1988-1991.

Strong, Emory. Stone Age on the Columbia. Portland: Binfords & Mort, 1959.

Zenk, Henry, Robert Boyd, and David Ellis. “Lower Columbia Chinookan Villages.” http://www.pdx.edu/

Zenk, Henry, Yvonne Hajda, and Robert Boyd. “Chinookan Villages of the lower Columbia.” Oregon Historical Quarterly 117.1 (Spring 2016): 6-37.