Marcus Whitman left his mark on Oregon Country as an early missionary to Cayuse people on the Columbia Plateau and as an advocate for American settlement of the region. His name is famous for the incident of his death at the hands of Cayuse antagonists in 1847, but his name is also affixed to a county in Washington State and a liberal arts college in Walla Walla, Washington.

Born in 1802, Whitman experienced a difficult boyhood separated from parents. Religious relatives and Congregational minister Rev. Moses Hallock contributed to his deep Christian faith. Unable to afford training as a minister, Whitman in 1832 attained a degree from reputable Fairfield Medical College and applied to serve as a medical missionary for the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM). In 1835, it sent him and Rev. Samuel Parker on a reconnaissance to determine if Oregon Country Indians desired missionaries. They met Nez Perce and other tribal members who desired a mission, and Whitman persuaded the ABCFM to send missionaries, including his new bride Narcissa, Rev. Henry Spalding, his wife Eliza, and William Gray. In 1836, the Whitmans established a mission at Waiilatpu in the Walla Walla Valley, while the Spaldings established their mission at Lapwai near the Clearwater River in present-day Idaho.

Whitman lacked theological training, so he could not baptize Indians, but he ministered by using his considerable Sunday school experience and telling Bible stories and teaching devotional songs. Many Cayuse enjoyed these activities, but they consistently rejected his strict Calvinism, while Whitman opposed Indian spiritualism, prompting religious disagreements. The Cayuse, however, were more willing to follow his agricultural teachings. Whitman traveled extensively as a physician providing drugs to missionaries and Indians, but he was dismayed when his Cayuse patients combined his treatments with those of shamans.

Whitman’s efforts at Waiilatpu soon became problematic. In 1838, a reinforcement of three missionary couples arrived, including Rev. Asa Smith, who quarreled with Whitman about missionary strategies. Smith’s negative correspondence to the ABCFM influenced its Oregon policy, and the arrival of Roman Catholic priests in Oregon posed competition for Indian converts. In the following year his daughter, Alice Clarissa, drowned. The distressed parents would not have another child, but they reared two mixed-blood girls. In 1841, an angry Cauyse chief struck Whitman and pulled his ears, a result of a disagreement when a few Cayuse leaders insisted on payment for occupying their land.

By the early 1840s, it was obvious that the Whitmans had failed to Christianize and acculturate the Cayuse. Marcus and Narcissa, like most Americans, were culturally arrogant. Frustration led Whitman to consider resignation, but he feared Catholics would occupy Waiilatpu. Furthermore, he believed a closure would weaken the American claim to Oregon. Thus the overworked couple continued to pursue unattainable goals.

In 1842, ABCFM reacted to negative letters from missionaries by recalling Smith and Gray, dismissing Spalding, and transferring Whitman to Tshimakain to join colleagues Cyrus Walker and Cushing Eells. Whitman traveled east and persuaded the ABCFM to rescind its orders. An ardent expansionist, he was certain that Oregon could be reached by wagons, and he urged Christian families to settle near Waiilaptu where they could help convert the Indians. Whitman served as guide and physician for a wagon train in 1843 that brought about a thousand settlers to Oregon.

From 1844 until his murder three years later, Whitman continued missionary tasks and provided food and sanctuary for immigrants. The Cayuse rightly worried about displacement by migrating whites and the Whitmans’ concentrated aid to whites and their neglect of the Indians. Ironically, by encouraging immigration and expansion, Whitman jeopardized the future of the Cayuse and his mission. Aware of his declining status, he pondered resigning in 1845, but like President Thomas Jefferson he was an optimist and insisted that the two races could share the land.

In the fall of 1847 a measles epidemic introduced by tribesmen, not by overlanders, led to massive deaths among the Cayuse. A band of Cayuse blamed Whitman for being a failed shaman or for being a murderer administering poison, and they murdered Marcus, Narcissa, and twelve others on November 29, 1847, an event known as the Whitman Massacre. The event led to the tragic Cayuse Indian War, which lasted for more than seven years and partially led to the Walla Walla Treaty of 1855.

-

![Whitman Mission buildings at Waiilatpu, about 1846.]()

Whitman Mission, Paul Kane sketch of, ca. 1846.

Whitman Mission buildings at Waiilatpu, about 1846. Sketch by Paul Kane, from Thomas Vaugan, ed., _Paul Kane, The Columbia Wanderer: Sketches, Paintings, and Comment, 1846-1847_, Oreg. Hist. Soc. Press, 1971, p. 16.

-

![Lithograph of Marcus Whitman murder.]()

Whitman, Marcus, Murder of, lith., bb000025.

Lithograph of Marcus Whitman murder. Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., bb000025

-

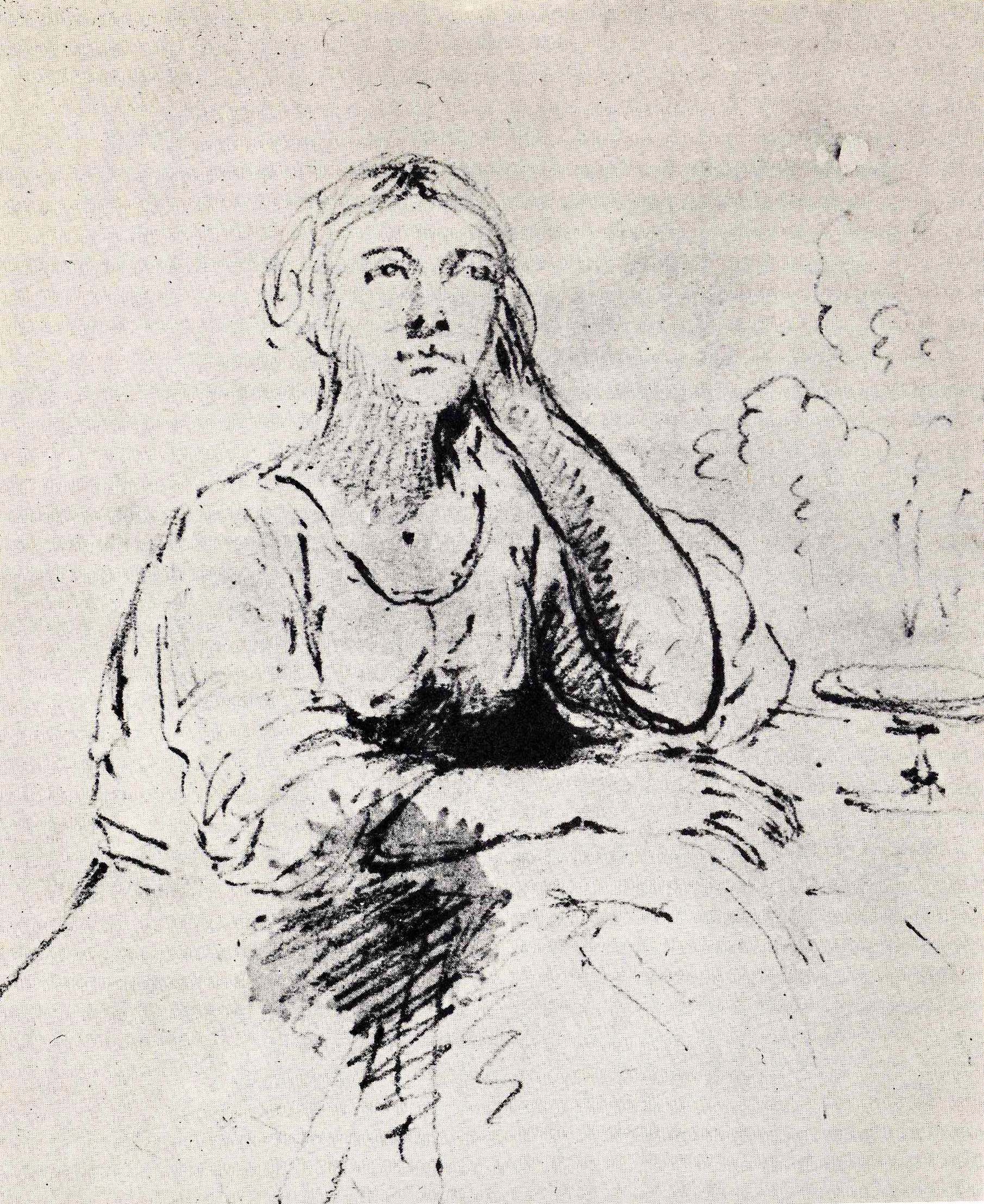

![Narcissa Whitman, about 1846.]()

Whitman, Narcissa, Paul Kane sketch of, ca. 1846.

Narcissa Whitman, about 1846. Sketch by Paul Kane, from Thomas Vaugan, ed., _Paul Kane, The Columbia Wanderer: Sketches, Paintings, and Comment, 1846-1847_, Oreg. Hist. Soc. Press, 1971, p. 52.

Related Entries

-

![Narcissa Whitman (1808-1847)]()

Narcissa Whitman (1808-1847)

Missionary Narcissa Prentiss Whitman is probably Old Oregon’s mos…

-

![Whitman Massacre]()

Whitman Massacre

The 1847 murders of frontier missionaries Marcus and Narcissa Whitman n…

-

![Whitman Massacre Trial]()

Whitman Massacre Trial

On November 29, 1847, Protestant missionaries Marcus and Narcissa Whitm…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Drury, Clifford M. Marcus and Narcissa Whitman and the Opening of Old Oregon vols. 1 and 2. Glendale, Calif., Arthur H. Clark Company, 1973

Josephy, Jr., Alvin M. The Nez Perce Indians and the Opening of the Northwest. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1965.

Karson, Jennifer ed., As Days Go By: Our History, Our Land, and Our People: The Cauyse, Umatilla, and Walla Walla. Portland: Oregon Historical Society Press, 2006.